The Air Battle above

Jianqiao[i],

China

August 14, 1937

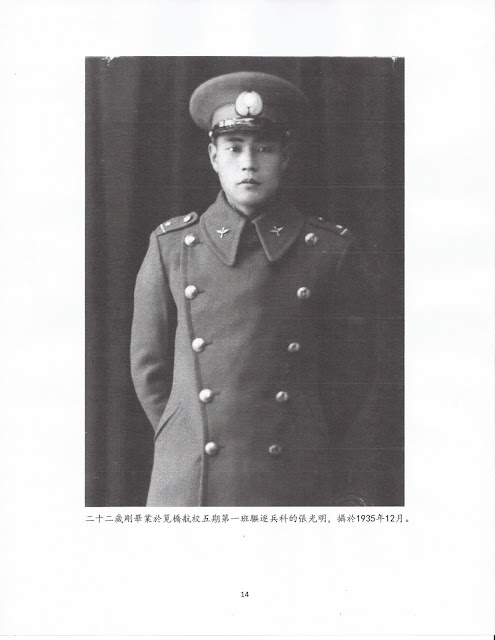

Witnessed by Chang Kwang Ming[ii],

a 102-year-old centenarian and pilot in the 22nd Squadron of the 4th

Pursuit Group of the Chinese Air Force during the War of Resistance

July 2015 on

the 70th anniversary of the Japanese Surrender

Los Angeles, CA

Over 77 years ago, I was a pilot in the

22nd Squadron of the 4th Pursuit Group of the Chinese Air

force. I took part in this renowned

air-to-air battle on August 14, 1937 against the Japanese Air Force.

Over the past 70+ years, I have read many articles on this air battle by people

reporting on or recalling this event. And these accounts vary. Why? I believe the answer is that none of these writers had

personally engaged in that air battle.

Due to the mishandling of documentary data, there are some accounts that

use hearsay, guesswork and

exaggeration. Some may have even

concealed some facts, resulting in gaps in the truth.

The

value of history is its truthfulness. As time passes, I feel, as a centenarian, a

sense of duty to give a firsthand account of the facts through my experience in hopes of providing

a correct historical record.

I.

After the Marco Polo Bridge[iii]

Incident of July 7, 1937

Missions and Activities of

the 4th Pursuit Group

The

Marco Polo Bridge incident near Beijing[iv]

on July 7, 1937, ignited an all-out Chinese War of Resistance against Japan. In mid-July, the 4th

Pursuit Group (PG) of the Chinese Air Force, stationed

at Nanchang[v], Jangxi

Province, received orders to

secretly fly to Zhoujiakou[vi],

Henan Province and to stand ready for further orders. At the time, they had three combat missions:

1. To

bomb the command post of the

Japanese barracks in the Nankai District in the city of Tianjin[vii].

2. To

bomb the six Japanese airplanes at the Bailingmiao Airfield[viii]

in Sueiyuan Province, now a part of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous District.

3. To

safeguard the new defense line around Baoding[ix], Hebei Province by

coordinating with the Chinese army to support the ground troops.

We

were on a high alert status, awaiting instructions to attack. The whole nation was in a dynamic, ever-changing

military combat situation. Yet, we had

not received any orders, so we did not carry out the above three potential

attack missions.

After

attending a military conference in Nanjing[x],

then the capital of China, on August 13, 1937, Gao Zhihang[xi],

the Commander of the 4th Pursuit Group, telegrammed our Pursuit Group

at noon. He ordered the whole Group to

immediately fly to Jianqiao Airfield (near Hangzhou[xii] city,

in Zhejiang Province) to await further orders while the commander himself flew

directly from Nanjing to Jianqiao. All

three squadrons under the 4th Pursuit Group, Nos. 21, 22 and 23, followed the order, taking off

in sequence toward the destination.

It

was a stormy afternoon, with heavy rain blurring visibility. Despite the risk, we flew at a very low

altitude. My squadron No. 22 zigzagged

the route in order to stop for refueling at Guangde Airfield[xiii],

Anhui Province. On the way, we spotted

unknown airplanes. Fight Leader Lo Yiqin[xiv]

and I wanted to verify and be ready to fire if they were enemy planes, but held

up because of the poor visibility. In

addition, the unidentified airplanes quickly disappeared into the clouds after

they saw us. And so, we continued on, flying

to Jianqiao.

Before

reaching the airspace above Jianqiao, I saw an inferno from distance and

realized that Jianqiao had been bombed. I followed Flight Leader Lo Yiqin. We broke away from the team and flew eastward

searching for the invading planes. Our effort was to no avail due to the

inclement weather conditions so after reaching as far as the area above the

Qiantang River[xv]

Estuary, we turned back.

Commander Gao,

Squadron No. 21 and Squadron 23 planes landed at Jianqiao before our Squadron No. 22.

They had encountered four

invading Japanese planes bombing the airfield. Flight Leader Lo Yiqin and I were the last two

planes of Squadron No. 22 to land. We

hurried to join the post-battle review session called by Commander Gao with all

of the 4th Pursuit Group members.

In the session, he described how he had shot down one Japanese Air Force

Model 96. We were thrilled and filled with admiration over this exciting

news. Then, he gave us instructions and

the formation to fly for our mission the next day, and ordered us to fill up

our fuel tanks and get our planes ready to fight. The time was around 5:30 p.m.

II. The Air Battle at Dawn August 14, 1937

Because of the bombing at Jianqiao, the Jianqiao

ground crew had evacuated to take shelter. Only a few men had returned.

Therefore, we had to arrange and prepare everything for our upcoming

mission without the usual ground crew support. The rail fueling car from the depot

was bombed in the afternoon, which was what caused the inferno I saw. Without the proper facilities to refuel the

planes, each of us had to make many trips carrying 5-gallon containers of

gasoline on our back to our individual planes.

With little on hand to use as tools, we resorted to using stones to pry

open each container. Then we carefully

assisted each other, two as a group, to cautiously pour the fuel into the

planes’ tanks, all the while getting drenched in the ongoing pouring rain. It was a time-consuming effort and took us

about six hours. By the time all the preparation tasks for the next mission were done, it was about 1:30 a.m. on the early

morning of August 14. None of us pilots

had eaten since noon the day before, August 13. We were hungry and cold, soaked

with rain, and totally exhausted.

We each then

randomly chose the instructor’s dormitory of the Chinese Central Aviation

Academy and changed

into whatever clothing was available in the room and grabbed a bit of rest. (The dormitory building was vacated, and all the

instructors and cadets of the Academy had evacuated to the southwestern part of

China.) Little time had passed when around 3 a.m., we were awakened by the shrill sound

of the air raid siren. We

scrambled and dashed toward our planes.

In

the darkness, we made an emergency take-off. The clouds hovered at around

3,000 feet and visibility was bad. To

avoid colliding with my colleagues’ planes above the airfield, I decided to fly southwards toward the south

bank of the Qiantang River scouting the area south of Hangzhou and Jianqiao, in

anticipation of where the enemy planes were heading in from.

At

dawn, I spotted a tiny, wiggling black line emerging from the southeast horizon.

It was far away but it was gradually getting closer. Then, instantly, this small black line

loomed large. It was a group of

airplanes. I pulled up higher and could identify that they were enemy

planes. I quickly switched to attack

mode.

I

observed that these enemy planes in formation were four large biplane bombers,

with the red sun emblem painted on their wings and fuselages. Immediately I set my sight on the lead plane, aimed directly at its front cockpit

and fired. Success! The plane was hit. It exploded into a ball of fire and

took a nosedive. After this attack, I peeled

away from the scene, turned my plane around and returned for the second attack.

Meanwhile, in the same airspace,

Flight Leader Zheng Shaoyu[xvi]

(Plane No. 2204) also shot down another enemy bomber. Then almost simultaneously, my other 3

colleagues’ planes attacked, hit and destroyed two other enemy planes. Within just about three minutes, a total of

four Japanese bombers were set ablaze and plummeted downward.

Upon review, after the attack,

verifying the enemy’s airplane models, we discovered that the planes that had

been shot down, were large model biplane bombers. They looked to be nonmetal Model 88, which

had fuselages that were fragile and flammable once attacked.

After our engagement with the Japanese

bombers, I flew my plane (no. 2205, a Curtis Hawk III) to get closer to Flight Leader Zheng

Shaoyu’s plane. We then flew in formation toward Jianqiao. After daybreak, I saw a large formation of

Japanese planes in the distant southwest flying toward Jianqiao.

I could see that they were being chased from behind and attacked by our

planes. The

enemy headed northeast, hurriedly

jettisoned bombs in the outskirts of Jianqiao, escaping eastward, disappearing

in the clouds. During this encounter, the Japanese suffered the loss of another two

planes.

Flight Leader

Zheng and I tried to intercept and attack these invaders by flying in a

straight line due east from the northern banks of Qiantang River into Pingshan[xvii]

airspace. However, we detected no enemy

planes when we reached the airspace between the Qiantang estuary and Jinshanwei[xviii]

, so we turned back to

Jianqiao.

After landing,

I learned that Commander Gao had suffered some shrapnel wounds in his left arm,

so he was sent to the Hangzhou Guangji Hospital, and that all my other

colleagues had flown back, landing safe and sound! While looking at each

other, we noticed that some were barefoot, some were wearing pajamas, some were

in their underwear, and others were soaking wet in their flying uniform.

Everyone was pale, blue in the lips, and shivering in the cold! Now, the time was around 6:00 a.m..

This August 14, 1937 aerial battle

marked the beginning of the 4th Pursuit Group’s engagement in

dogfights with the Japanese planes, which then began to occur around the clock.

We supported the ground troops and naval combat units in the areas above

Shanghai[xix],

Nanjing and Hangzhou.

Three weeks after this decisive air

battle, at the Daxiaochang[xx]

Air base at Nanjing, Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek[xxi]

pointed out, “The Chinese Air Force in the past three weeks routed the Kirasuru[xxii]

Air Force. As a result, their Commander

committed hari-kari/suicide. This

resounding victory was because of the fighting spirit of our Air Force. They gave their all!”

III. Corrections to the Previous

Accounts of August 14, 1937

Over seventy seven years ago, I was

one of the pilots taking part in this “8.14” air battle and the one who first

discovered, engaged, attacked and shot down the enemy plane. In the past many years, I have read many

related articles on this event. There

are so many different accounts, that I am compelled to make some

clarifications.

In one account of the “8.14” air battle, it is recorded

that the Chinese Air

force destroyed six Japan Model 96 bombers with no loss of our planes.

Another account claims the battle shot down two Japanese

Model 96 bombers with zero loss in a 2:0 triumph.

A third account states that the Japanese Air force

suffered a loss of two planes while the Chinese Air Force lost one.

As an eyewitness and participant, I

would like to correct these accounts.

1.

The

first account, while correct that the total number of planes shot down was six,

inaccurately notes that all the planes were Model 96 bombers. Four of the six

were large-scale model biplane bombers, most likely Model 88. Only two were Model 96. The reason for this deviation most likely was

that people on the ground in the vicinity of Jianqiao only saw the two groups

of invading planes in formation which were all Model 96 bombers. It is likely that they also saw the two

planes shot down over the northwest hillsides and the southeast suburb of

Jianqiao which were Model 96 bombers. As a result, people may have assumed that

all the planes shot down were the same model aircraft. Very few people witnessed the battle at dawn

on August 14 and the falling of those 4 slow, lumbering Model 88 biplane

bombers. The recorded history that six

Model 96 planes were shot down that day is erroneous, and needs to be corrected.

2. The second account of two Japanese planes

being shot down could have resulted from people only witnessing the two planes

which were shot down in the air space in the Jianqiao area, not knowing that

the air combat had already broken out earlier above the south bank of the

Qiantang River and that four Japanese biplanes had been shot down there.

3. The third version with the two Japanese

losses to one Chinese loss was the official Japanese account, which concealed

the actual military performance in order to mislead the Japanese people and

Japan’s enemies. The single plane

claimed to be shot down by Japan could be the plane of Liu Shufan[xxiii],

which accidentally crashed on August 13, 1937 killing him. There were no Chinese Air Force plane

casualties on August 14. On that day of battle,

Commander Gao had his left arm injured.

Both he and his plane safely landed at Jianqiao Airfield.

IV. “8.14” – Air Force Day of China

The August 14 battle was the first

ever large-scale air-to-air battle in China.

This 6:0 victory over the invading Japanese forces helped us to record

in history a brilliant first chapter of the Chinese Air Force.

Early in the war, the Japanese Air

Force had absolute superiority over us.

In terms of quantity, the number of its airmen far outnumbered us by

12:1. As for quality, whether of

aircraft capability, military training or caliber of people, the Japanese Air

Force had significant advantage over us.

Yet, our young airmen were undaunted by their disadvantages. These untested young pilots with their valor

and intelligence, on that one day, shot down six attacking bombers. They emerged totally unscathed without any

casualties.

Once the news was public, the whole

country rejoiced over this morale booster.

To commemorate this first air-to-air complete victory August 14 (“8.14”)

was declared Air Force Day in China.

This “8.14” feat reinforced our

conviction that, even as underdogs, we could win the fight by playing to our

strengths, by picking our battles carefully and by concentrating our firing

power. This air battle experience had a

long-lasting impact on our hard-fought eight year War of Resistance, signifying

the national unbroken fighting spirit of all the Chinese people against

Japanese aggression.

The article was translated by Debbie Cheng, 寇蕩平 (臺北空小)

No comments:

Post a Comment